By Rebecca Latta

The worst plant-damaging high heat event I’ve seen in my career happened in early July of this year, affecting plants in the San Gabriel Valley and throughout the Southern California region. Many of you have asked for help on how to manage your trees and gardens in such a severe event. I’m responding with some tips gained from my 25 years of experience promoting healthy trees and landscaping. If you have questions, please do call on me to assist you, 626-272-8444.

In the record-busting heat wave in July, mature trees dropped green leaves, buds and fruit, plants wilted, sunburned and scorched. Shoots, seedlings and potted plants wilted and died. What caused it? Climate change is promoting heat events and drought conditions here and around the world. More extreme weather events of this nature are expected, and will continue. We need to learn strategies to protect our trees and landscaping, which I outline below.

This garden, protected by a top layer of mulch, features drought-tolerant native oaks and sycamores.

This garden, protected by a top layer of mulch, features drought-tolerant native oaks and sycamores.

Choose the right species

Climate change presents significant challenges to the future of our urban landscape. As our once-mild Mediterranean climate heats up, we have to choose species that can adapt. Species such as redwood, birch, saucer magnolia, Victorian box and avocado tend to struggle in extreme heat events, and may need to be protected from heat and intense reflected light, or replaced with local natives, such as oaks and sycamores. Heat tolerant species from South America and the Sonoran desert, such as tipu, mesquite, desert willow, velvet ash, pinyon pine, California juniper, red willow, desert apricot and cypress may also be good choices.

Plant for both drought and heat resistance

Some plants from coastal climates can take dry soil but are not genetically adapted to high temperatures. Plants that thrive in hot conditions can feature waxy leaves, smaller leaf surface area, reflective surfaces or blue-gray color to reduce heat absorption, or can be drought deciduous, dropping leaves during dry parts of the year. Some plants store water below ground in roots or above ground in stems.

Heat damage can make plants more susceptible to opportunistic diseases and wilt, chlorosis and fruit drop. Excessive heat and sunlight can speed up disease issues. Reflected heat can do damage. Plants near hardscape, artificial turf and on sunny walls with a southern or eastern exposure can be scorched or burned. High soil temperature damages seedlings and may cause root and tissue damage that shows up later in trees and shrubs.

Burlap shade cloth protects this tomato plant.

Implement cooling strategies during the event

Provide shade. Plan ahead and plant tall annuals like sunflowers to shade smaller plants. During the heat event, use shade cloth, cardboard and patio umbrellas to protect plants from heat. Protect mature shade trees that are shading other plants in the landscape, and keep them well hydrated prior to high heat events. Wrap burlap on exposed trunks, or use a foliar spray, whitewash or latex paint on trunks for sunburn protection. Shade can also be sprayed on plants and trees in the form of a clay product called Kaolin that reflects sunlight, much as we use zinc oxide as a sun block. Apply with an inexpensive sprayer. Be sure to follow package directions and wear a mask and goggles.

Water strategically

Water to establish deeper roots – less frequent deep irrigation in the spring and fall. During the summer, watering may need to be based on the weather—weekly or monthly—even for established trees. Get ahead of any high heat events and water deeply several days in advance of the event.

Soak plants to 1-2 feet deep, and allow the top one or two inches to dry out before watering again. Make sure water is reaching the roots at and beyond the drip lines of plants. Check moisture with an inexpensive moisture meter, with a small shovel or long screwdriver.

Mulching, blowing and pruning

Mulching is the best way to protect soil and plant roots from heat. It’s also key to conserving water. Mulches hold moisture, encourage soil microbial activity, suppress weeds and improve soil structure.

As you phase out heat-and drought-sensitive plants and plant new trees and shrubs that can tolerate drier and hotter environments, be sure to chip and spread them on-site as valuable mulch. Your old plants can help protect your new plants and provide food for their growth.

Apply bark chip mulch or mulch/compost mix about 4 inches deep around plant roots. Don’t use rocks or inorganic mulch—it can retain heat in the soil at night when roots need to cool down. Artificial turf should not be used—it can overheat soil, damaging roots.

Keep your mulch in place, don’t blow it away. Plants need this organic cover to protect the roots from heat and drying. Remind gardeners that blowers are for paved surfaces only. Keep dropped leaves in planter beds—leaf litter is good plant food.

Remove understory competition such as ivy, creeping fig and vinca. These plants can take water and nutrients away from trees and shrubs. Mulch these areas or plant sparsely.

Resist the urge to prune. Keep dead leaves on plants and trees until cooler fall weather. Those dead leaves will offer some sun protection for the rest of the summer.

Patio umbrellas provide protection for squash and pumpkin vines

Wait until fall to plant and fertilize

Plant new shrubs and trees in the fall, after the weather starts to cool off. Encourage new root and shoot growth by using products with potassium, that strengthens cell walls.

Don’t fertilize during a heat event. When you do fertilize, use products that strengthen cell walls. If soil is so dry it repels water, buy a wetting agent to penetrate the soil.

Warm Regards,

Rebecca

Photo by azarius/Flickr CC

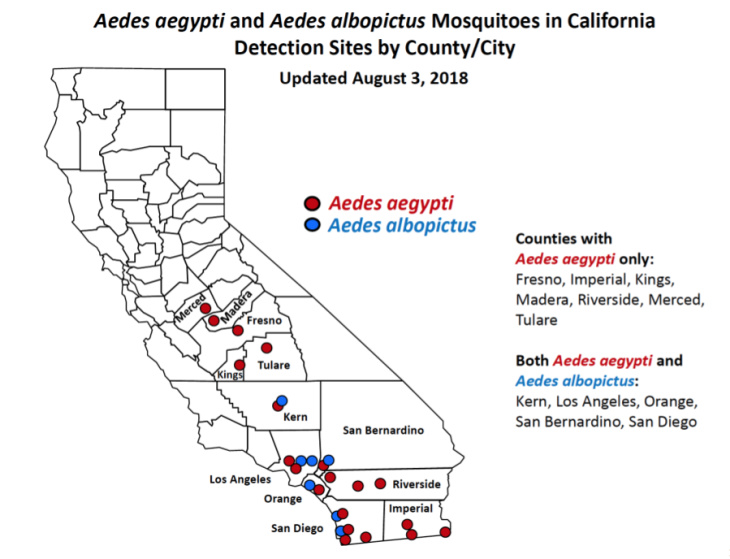

Photo by azarius/Flickr CC The distribution of invasive Aedes mosquitoes in Southern California, as of Aug. 3, 2018. (Courtesy California Department of Public Health)

The distribution of invasive Aedes mosquitoes in Southern California, as of Aug. 3, 2018. (Courtesy California Department of Public Health)

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/11488971/GettyImages_84543459.jpg)