Early detection increases the chances of eradicating pests

January 24, 2023

Trees provide shade to keep us cool, produce oxygen for us to breathe and calm our nerves. Numerous studies have demonstrated that even brief contact with trees and green spaces can provide significant human health benefits such as reductions in blood pressure and stress-related hormones. Trees also reduce noise and visual pollution, help manage storm water runoff, reduce erosion and provide habitat for birds and wildlife. Trees naturally capture carbon, helping to offset the forces of climate change. They also increase the value of our properties and communities. In short, trees are essential to our well-being.

Unfortunately, invasive pests pose an ongoing threat to California’s forests in both urban and wildland settings. Invasive insects such as goldspotted oak borer and invasive shothole borers have killed hundreds of thousands of trees in Southern California and are continuing to spread. Meanwhile, other pests and diseases such as Mediterranean oak borer and sudden oak death are killing trees in Northern California.

While the situation may sound dire, it is not hopeless. Of course, the best way to stop invasive pests is to prevent them from entering the state, as the California Department of Food and Agriculture has done on many occasions. For example, several months ago, CDFA border inspectors seized a load of firewood containing spotted lanternfly eggs (a pest that is causing extensive damage on the East Coast). When pests do sneak in, the next defense is to catch them early before they become established. Finally, even if pests do become established, they can be managed if not completely eradicated.

A few examples may help to illustrate why invasive tree pests deserve action, but not panic.

Red striped palm weevil eradicated in Laguna Beach

When red striped palm weevil, a highly destructive palm pest native to Indonesia, was discovered in Laguna Beach in October 2010, a working group was quickly formed to develop a management plan. The small but diverse group included international palm weevil experts, research scientists from University of California Riverside, CDFA and U.S. Department of Agriculture, UC Cooperative Extension personnel from San Diego, Orange and Los Angeles counties and county entomologists from the agricultural commissioner’s offices in Orange and San Diego counties.

The resulting response included a pheromone-based trapping program, public advisory and targeted insecticide treatments. Within two years, additional trapping and inspections could not find any signs of continued infestations. Early detection was key to the success: the infestation in Laguna Beach was identified early, so the weevil population was still relatively small. In addition, Laguna Beach is geographically isolated, the local climate is much cooler than the weevil’s place of origin, and the eradication effort was well funded by state and federal agencies. Eliminating invasive pests where such conditions are not present may prove more difficult.

Invasive shothole borers attack Disneyland

The Disneyland Resort in Anaheim contains 16,000 trees and over 680 different tree species. When park officials identified an infestation by invasive shothole borers in 2016, their initial attempts at vanquishing the insects with pesticides produced mixed results. Then, they consulted with experts from UC Riverside and UC Cooperative Extension and together designed and followed an integrated pest management program that included monthly ground surveys, a trapping program that helped to detect infestation hot spots and find and remove the source of beetles, and occasional pesticide treatments on selected trees. The park went from a large number of beetles in 2017 to very low levels today. There are still some beetles, but resulting damage is extremely low, and although monitoring programs continue, the park’s landscape team has been able to turn its focus elsewhere.

Goldspotted oak borer spotted in Weir Canyon

When goldspotted oak borer was confirmed in Orange County’s Weir Canyon in 2014, a team from Irvine Ranch Conservancy, the organization that manages the area on behalf of Orange County Parks, sprang into action. UC Cooperative Extension and the US Forest Service assisted IRC in developing a management program, and over the ensuing years, IRC has actively collaborated with OC Parks, The Nature Conservancy, OC Fire Authority, and CAL FIRE to control the existing infestation and stop its spread. IRC has surveyed the oaks in the area yearly to monitor the infestation and guide each year’s management actions.

To reduce the spread of the infestation, IRC removed more than 100 severely infested oaks in the first few years of management (no severely infested oaks have been found in the last few years of surveys). Additionally, more than 3,000 tree trunks have been sprayed annually in the late spring to kill emerging adult beetles and newly hatched offspring.

In the most recent survey of the oaks in Weir Canyon, the IRC team found only 12 trees with new exit holes, and most of those had just one to two exit holes per tree, which is an extremely low number. With the situation well under control, IRC is now considering modifying its annual spraying program and adapting other less aggressive treatment options. Finally, IRC has been actively planting acorns to mitigate losses due to the removals as well as the Canyon 2 Fire of 2016.

As these brief examples demonstrate, insect pest infestations can be managed or even eradicated if caught early enough. Early detection not only increases the chances of success, but also minimizes the cost of pest management efforts.

What you can do to prevent infestation

While management actions will vary depending on the insect or disease, species of tree and location, there are a few steps that will lead to greater success in fighting tree pests and diseases.

-

Keep your trees healthy. Proper irrigation and maintenance go a long way toward keeping trees strong and resistant to pests and diseases.

-

Check your trees early and often for signs and symptoms of tree pests and diseases. These may include entry/exit holes, staining, gumming, sugary build-ups, sawdust-like excretions, and branch or canopy dieback. Use available tools like the UC IPM website to determine probable causes of the problems.

-

Talk with experts (arborists, pest control advisers, researchers and advisors from the University of California and other institutions), and report pest findings to your county Agricultural Commissioner.

-

Evaluate the extent of tree damage and determine a management plan. Remove severely infested branches and trees that may be a source of insect pests that can attack other trees.

-

Properly manage infested wood and green waste. Chip wood and other plant materials as small as possible. Solarization or composting can further increase the effectiveness of chipping. It is generally best to keep those materials close to where they originated, but if you absolutely need to move them, first make sure the facility where they will be sent is equipped to process them. Always tightly cover materials while in transit. If working with a tree care professional, insist that proper disposal is part of the job requirements.

-

Many invasive tree pests can survive in down wood for long periods. When buying or collecting firewood, always obtain it as close as possible to where you are going to burn it and leave leftover firewood in place.

Randall Oliver is UC Statewide IPM Program Communications Coordinator.

Source: University of California Division of Agriculture and Natural Resources

Photo by azarius/Flickr CC

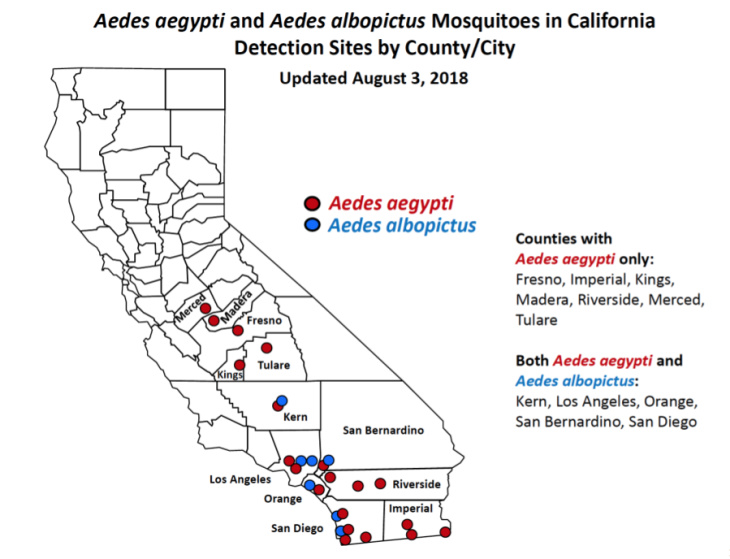

Photo by azarius/Flickr CC The distribution of invasive Aedes mosquitoes in Southern California, as of Aug. 3, 2018. (Courtesy California Department of Public Health)

The distribution of invasive Aedes mosquitoes in Southern California, as of Aug. 3, 2018. (Courtesy California Department of Public Health)